UPDATE: The best demo I have seen so far of many of DFXP’s features is at http://www.w3.org/2009/02/ThisIsCoffee.html.

The W3C has published a third last call for the draft specification of DFXP, the Distribution Format Exchange Profile for the Timed Text Authoring Format – or short: for their new standard format for captions. Comments are due by the 30th June, so rush if you want to give any feedback. Here is what came to my mind as I was reading the 183 pages long document.

Please note: This review looks at DFXP from a Web view, i.e. how compatible is it with existing Web technologies, since my main use case will be on the Web, even if advocates will say that that’s not it’s main purpose, strangely enough, for a standard coming out of the W3C.

The state of affairs with caption formats

When it comes to caption and subtitles, there is no lack of formats. It seems, because it is an easy challenge to define a data format for something as simple as a piece of text and some timing information, every new project that wanted to deal with captions – or more generally timed text – created their own format. I am no exception to the rule. 🙂

Thus, the current state of affairs wrt timed text is that there are many different textual file formats to store such data, there are also many different video container formats each with their own data format (or even formats) for embedding timed text into them, and there is a lot of software that will deal with many input, output and encapsulation formats.

The problem with this situation is that the formats are all different in their complexity. The simple “piece of text and timing information” problem can be turned into as complex a problem as you desire. By adding layout information, styling information, animation functionality, metadata about the video and about the content, and possibly hyperlinks, we have ended up in a large mess of incompatible formats.

The aim of W3C Timed Text

The W3C Timed Text working group was chartered in January 2003 to attack this issue. It was supposed to become the super-format of all possible functionalities for timed text formats and therefore a perfect interchange format between applications (see requirements document). Its focus was for use on the Web and with SMIL and to make use of existing W3C technologies where possible

However, the history of captioning is TV and the scope of Timed Text is beyond mere use on the Web, so while W3C Timed Text took a lot of inspiration from other Web standards, it has become a stand-alone standard that does not rely on, e.g. the availability of a CSS engine, and it has no in-built hyperlinking functionality (see what requirements it fulfills).

Dissecting DFXP

So. let’s look into some of what DFXP provides.

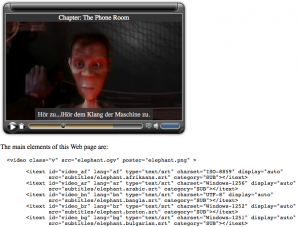

Here is an example file taken straight from the draft – check the presentation here:

<tt xml:lang="" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2006/10/ttaf1">

<head>

<metadata xmlns:ttm="http://www.w3.org/2006/10/ttaf1#metadata">

<ttm:title>Timed Text DFXP Example</ttm:title>

<ttm:copyright>The Authors (c) 2006</ttm:copyright>

</metadata>

<styling xmlns:tts="http://www.w3.org/2006/10/ttaf1#styling">

<!-- s1 specifies default color, font, and text alignment -->

<style xml:id="s1"

tts:color="white"

tts:fontFamily="proportionalSansSerif"

tts:fontSize="22px"

tts:textAlign="center" />

<!-- alternative using yellow text but otherwise the same as style s1 -->

<style xml:id="s2" style="s1" tts:color="yellow"/>

<!-- a style based on s1 but justified to the right -->

<style xml:id="s1Right" style="s1" tts:textAlign="end" />

<!-- a style based on s2 but justified to the left -->

<style xml:id="s2Left" style="s2" tts:textAlign="start" />

</styling>

<layout xmlns:tts="http://www.w3.org/2006/10/ttaf1#styling">

<region xml:id="subtitleArea"

style="s1"

tts:extent="560px 62px"

tts:padding="5px 3px"

tts:backgroundColor="black"

tts:displayAlign="after" />

</layout>

</head>

<body region="subtitleArea">

<div>

<p xml:id="subtitle1" begin="0.76s" end="3.45s">

It seems a paradox, does it not,

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle2" begin="5.0s" end="10.0s">

that the image formed on<br/>

the Retina should be inverted?

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle3" begin="10.0s" end="16.0s" style="s2">

It is puzzling, why is it<br/>

we do not see things upside-down?

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle4" begin="17.2s" end="23.0s">

You have never heard the Theory,<br/>

then, that the Brain also is inverted?

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle5" begin="23.0s" end="27.0s" style="s2">

No indeed! What a beautiful fact!

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle6a" begin="28.0s" end="34.6s" style="s2Left">

But how is it proved?

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle6b" begin="28.0s" end="34.6s" style="s1Right">

Thus: what we call

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle7" begin="34.6s" end="45.0s" style="s1Right">

the vertex of the Brain<br/>

is really its base

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle8" begin="45.0s" end="52.0s" style="s1Right">

and what we call its base<br/>

is really its vertex,

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle9a" begin="53.5s" end="58.7s">

it is simply a question of nomenclature.

</p>

<p xml:id="subtitle9b" begin="53.5s" end="58.7s" style="s2">

How truly delightful!

</p>

</div>

</body>

</tt>

I’m going to look at each of the different functionalities separately and discuss their strengths and weaknesses.

Content

Let’s begin with the body of the DFXP document and what elements are defined for this area.

Firstly, <body> comes with optional begin, end, and dur attributes. As is the case for all time specifications in DFXP, there are both “end” and “dur” attributes. Why this over-specification? There is not even an explanation which of the two has higher priority when in conflict. This is plainly asking for trouble – why not simplify the spec?

The “region” and “style” attributes refer to a previously defined region and styles that are applied to the body. “id” and “lang” attributes allow to associate a name and a language with the body.

The “timeContainer” attribute enables the author to specify whether the elements in the body are all to be regarded as temporally parallel or in sequence, the default being parallel. This means that all text elements specified inside the body can render over the top of each other – a situation that is solved by giving them specific start and end times.

The containing elements of body are a sequence of <div> tags. The div element functions as a logical container and a temporal structuring element for a sequence of textual content units. div elements like body elements are allowed a “start”, “end” and “dur” attribute and generally everything that the body element also has, except that their children can be more div or p. Again, the children of the div element are all regarded as being temporally parallel.

The p element is basically the inner-most element that contains the actual text, including new-lines (br) and spans to associate further styling, metadata, or animations. The children of the p or span element are also all regarded as being temporally parallel, unless otherwise specified.

The structuring of text into div, p, and span elements seems to make sense and provide sufficient (if not even excessive) flexibility for any required timed text needs.

Layout

Once the text is specified and structured, the next question is where it should be positioned.

The extent attribute of the <tt> root element specifies the width and height of the root container, if not specified by the external authoring context.

Inside the root container, regions are defined through explicit <region> elements. The origin of placement for a region is the top left corner. Regions can define their “origin” offset, their “width” and “height”, the alignment of text within them through the “textAlign” and “displayAlign” styles, and whether text that “overflows” a region should be visible or hidden.

The way in which DFXP defines regions and placement of text within regions is very different to the way in which HTML and CSS work. By default, elements in HTML flow one after another in the same order as they appear in the source. CSS attributes applied to the elements can control their positioning through giving coordinates, or relative placements in relation to other elements. In DFXP elements are placed inside regions that are styled, making it incompatible with HTML.

Styling

The styling attributes available for DFXP are limited, but sufficient for timed text purposes. The way in which style associations to elements are resolved is quite diverse. Styles can be associated with regions, with individual elements, individually and as a group, through layouts and through parent elements. Compared to CSS, it feels complicated and potentially full of contradictions.

Animation

Further to styling, DFXP defines animations, which are discrete changes to some style parameter value that applies over some time interval. This is relevant for example to implement karaoke style colouring of text over time.

Metadata

The <metadata> element serves as a generic container for grouping metadata information. It can be associated virtually with any element – which seems somewhat over-flexible, but provides for interesting meta data information such as meta data for styles or for a <br>.

In addition, metadata is actually limited to a set number of elements: title, desc, copyright, agent, name, and actor. These are strange fields – in particular if you compare them to the flexibility of HTML meta data, which consists of free-form name-value pairs, bringing us domain-specific schemes such as the Dublin Core. This is not easily possible here, but instead one has to define extensions to allow for such flexible meta data.

Other features

DFXP provides other features such as information that describes the related video file, e.g. frameRate, subFrameRate, frameRateMultiplier, pixelAspectRatio, smpteMode, timeBase, and tickRate. Such information will help at the point in time when DFXP is supposed to be multiplexed into a binary media file together with audio and video tracks. These attributes can provide information required for the multiplexing process. I am not sure that justifies their existence though.

Other, minor features are available too. Check out the full specification to get a complete picture.

Examples

Part of the publication of this draft is also a test suite. Several of the defined features are still not represented in the test suite, which to me raises the question if they are really required. It might do wonders to the draft size to remove them.

Summary

DFXP is a standard for timed text that is firmly grounded in past captioning specifications, but written in XML, and borrowing ideas from Web technologies. It is unfortunately not re-using existing Web infrastructure to implement its more complex features: no use of CSS for styling and layout, no use of hyperlinks. Also, the use of namespaces seems excessive and won’t make it easy to author this format, in particular since the defined namespaces do not map into the defined profiles.

DFXP is, however, simple to transcode to something that a Web Browser can deal with through its existing engines, because it has borrowed from other Web standards. It is thus easier to work with on the Web than most other formats. It should be relatively easy to map to HTML, CSS and javascript, as already started in the test suite with the HTML5 video element.

DFXP is witten in such a way that it is possible to put together a new profile with extensions that are more appropriate for specific needs, e.g. that fit better into existing Web infrastructure. Currently, DFXP has three defined profiles: one focused on transformation, one focused on presentation, and one that contains everything.

I think it’s time for a html5 profile of DFXP that at minimum extends DFXP with hyperlinks, making it a real timed text Web format.